News

The Differences Between Dark and Amber Rosin

Update: 1/4/2013

Rosin, the ubiquitous accessory for any stringed-instrument player is actually a bit of a mystery to most musicians. Few know how it's made, how it works, and which types or grades are best for their instruments.

Standing in front of the accessory counter at your local violin shop and trying to pick out a cake or box of rosin is a bit like standing in front of the bar at your local pub: Do you choose dark or amber, winter or summer?

To help decode the mystery, here is some valuable information on that little box of rosin hiding in your instrument case’s accessory compartment.

What Is Rosin Exactly?

Rosin—colophon or colophony, as it is known to luthiers—is a resin collected from one of 110 different types of pine tree throughout Europe, Asia, North America, and New Zealand. The name colophony harkens back to the ancient city of Colophon in Lydia, which produced a high-grade of resin originally used to create smoke for both medical and magical procedures.

Rosin is drawn directly from living trees in a tapping process–in much the same way that maple syrup is collected (the process in no way harms the tree). First, a small area of the tree's outer bark is removed. Then the tree is fitted with a drip channel and collection container. Finally, the tree is cut with V-shaped grooves about 1 cm (.39 inch) wide just above the drip channel.

These marks induce the flow of resin into the container (the cuts must be renewed every five days or so to ensure the continuous flow of tree resin).

These marks induce the flow of resin into the container (the cuts must be renewed every five days or so to ensure the continuous flow of tree resin).

After the resin is collected, it is sometimes mixed with other tree saps—usually from larches, spruces, or firs—to create a specialized formula (rosin makers are as secretive about their individual recipes as violin makers are with varnish).

This formula is then purified by straining and heating it in large vats until the resins are completely melted. Once cooked, the concoction is poured into molds.

After the mixture sets for about 30 minutes, the rosin is smoothed down and polished. Rosin is packed into a swath of cloth or fitted into a tight-sealing container.

This formula is then purified by straining and heating it in large vats until the resins are completely melted. Once cooked, the concoction is poured into molds.

After the mixture sets for about 30 minutes, the rosin is smoothed down and polished. Rosin is packed into a swath of cloth or fitted into a tight-sealing container.

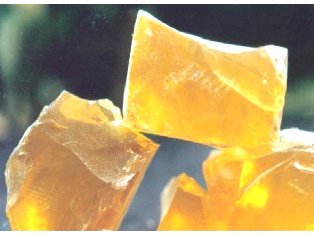

The color of rosin is dictated by the time of year during which it is collected. If the resin is tapped in late winter or early spring, it will be gold or amber in color and hard when set up.

As the seasons change to summer and fall, the color of the resin darkens and the consistency softens.

As the seasons change to summer and fall, the color of the resin darkens and the consistency softens.

How Rosin Works

"The first impression that I always have to work with is that bow hair has scales on it that grab the string and make it vibrate, which is not at all the case," says renowned acoustics expert Norman Pickering in a recent chat with Strings author James McKean (read our November/December 2003 Shop Visit for the full story).

"It is the adhesion of the sticky rosin between the bow hair and the string that makes it work. The bow pulls the string in the direction of the bow motion until the adhesion breaks—you get to the point where it can't pull anymore. The string snaps back and vibrates at whatever frequency it's tuned to."

"It is the adhesion of the sticky rosin between the bow hair and the string that makes it work. The bow pulls the string in the direction of the bow motion until the adhesion breaks—you get to the point where it can't pull anymore. The string snaps back and vibrates at whatever frequency it's tuned to."

This is one of two schools of thought regarding how sound is produced on a bowed stringed instrument. Others say that the rosin causes the "barbs" or scales on the bow hair to stand up rather than lie flat.

These barbs catch the string when the bow is drawn, creating vibrations. No matter which ideology you subscribe to, there is no disputing that rosin is a key ingredient in making music.

These barbs catch the string when the bow is drawn, creating vibrations. No matter which ideology you subscribe to, there is no disputing that rosin is a key ingredient in making music.

Choosing and Using Rosin

When purchasing rosin, first sort out whether you're looking for a student- or professional-grade product. Student-grade rosin is cheaper, often has a grittier sound, and produces more powder than the professional grades.

For some players, such as fiddlers, this is a plus. But classical players may find that the higher-priced professional-grade rosins better fit their needs. Professional-grade rosin is created from a purer resin and generally produces a smoother, more controlled tone.

For some players, such as fiddlers, this is a plus. But classical players may find that the higher-priced professional-grade rosins better fit their needs. Professional-grade rosin is created from a purer resin and generally produces a smoother, more controlled tone.

Next, decide between light, or amber, and dark rosin–sometimes also defined as summer (light) and winter (dark) rosin. Dark rosin is softer and is usually too sticky for hot and humid weather—it is better suited to cool, dry climates.

Since light rosin is harder and not as sticky as its darker counterpart, it is also preferable for the higher strings. "[Any type of] rosin—except for bass rosin, which is much, much softer and would make a mess on a violin bow—pretty much works on any instrument," says Richard Ward of Ifshin Violins in Berkeley, California.

"Lighter rosins tend to be harder and more dense—a good fit for violin and viola. Darker, softer rosins are generally preferred by the lower strings."

Some companies also add precious metals to their recipes—another choice to consider when shopping for rosin. It is not uncommon to see gold, silver, lead-silver, and copper added to rosin. These materials purportedly increase the rosin's static friction, creating different tonal qualities.

Gold rosin is said to produce a warm, clear tone and is appropriate for all instruments. The addition of gold to the rosin mixture can soften a harsh-sounding instrument.

Solo performers often find that gold rosin helps them produce a clearer, more defined tone.

Solo performers often find that gold rosin helps them produce a clearer, more defined tone.

Silver rosin creates a concentrated, bright tone and is especially good for performance in higher positions. It is best suited for the violin or viola.

Lead-silver rosin is well-suited for both the violin and viola and is a soft but nontacky rosin. It enhances warmth and clarity, producing a fresh playing tone.

Lead-silver rosin is well-suited for both the violin and viola and is a soft but nontacky rosin. It enhances warmth and clarity, producing a fresh playing tone.

Copper is the most defined of all the rosin additives. These rosins can help make playing easier for a beginner (and are said to be the best for 1/2- and 3/4-size instruments). Copper creates a very warm, almost velvety-soft tone. This rosin is also popular among gamba players.

Source: http://www.allthingsstrings.com - By Heather K. Scott

Source: http://www.allthingsstrings.com - By Heather K. Scott